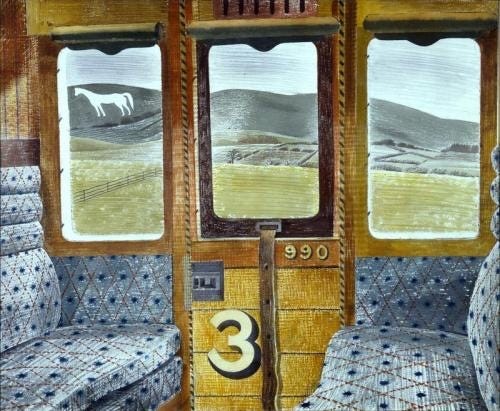

A window on our world

A reflection on “Train Landscape” (Rivilious, Eric; 1940) as a metaphor for our psychodynamic minds

The publication of Frances Spalding's magnificent volume "The Real and the Romantic: English art between the two world wars" (Spalding 2022) is itself a therapeutic exercise. She mines the art of the period, so distant yet familiar to us, situating it in the historical context. The beautifully illustrated book reads like a family album of a long-lost grandparent. The art of the period evokes the dreams, absurdities, and nostalgia felt by our grandparents in that brief interwar period, tinged by rising fear and anxiety as the 1930s draw to a close. The album is now down from the shelf and open in our hands.

Amongst the comprehensive survey, Spalding manages to restore the work of Eric Rivilious as a significant British artist and the reputation of landscape and watercolour painting alongside this. Although Rivilious's landscapes can be enjoyed for their airy, expansive feel, not unlike a latter-day John Sell Cotman, its geometry and angularity have a distinctly modernist vibe. In walks like Chalk Paths (1935) and Cuckmere Haven (1939), the scenes are empty and barren, the angles appear discordant, and the presence of barbed wire introduces a discordant note. Barbed wire in the middle of a field would likely have evoked deeply repressed experiences for people living in the interwar years.

As Spalding writes,

"His landscapes are mostly seen under a chilly grey sky, and when the sun does appear in one corner, it rarely warms the scene. An understated melancholy imbues many of the interiors he painted, which, like his landscapes, make use of the angular recession that leaves his designs taut and strained." (Spalding 2022)

And,

"Far from being bucolic, they convey a brittle tension which is modern". (Spalding 2022)

Taut. Strained. Brittle. This is how the artist conveyed the sign of the times.

When we view "Train Landscape", we can see the scene simply as an inviting, comfortable space that is very familiar to most of us. We notice empty seats facing each other and three window pains looking out onto a landscape. The image of the Westbury Horse hangs in the landscape, reminding us of the archaic forms and the timeless interaction between people and the landscape, further emphasised by the fences and stone walls dividing up the fields.

At a glance, we might not give the scene too much thought. We might notice its quaint feel, although, to Rivilious, the railway carriage probably appeared relatively new, emphasising the contrast between the train's modernity and the countryside's timelessness. Yet, if we pay attention, there is much more we can look at and experience in this scene.

Firstly, the carriage is empty. It's a space, a container for us to fill. Is this an adventure, a journey filled with promise? Or is it full of foreboding and worry? Is it a time to enjoy, read a good book, write that novel, or simply stare out the window wistfully? This depends on us and what we bring to this space.

The photographic and discordant angles of the picture create a dynamism to suggest anything could happen. Train carriages are not neutral spaces and never have been since Hitchcock. After The Lady Vanishes of 1938 (Hitchcock 1938) , no railway carriage will ever be quite the same again. "There's no English lady here!" "You all think I'm crazy, but I'm not! I'm not!" (Hitchcock 1938).

Psychoanalytical ideas were plugged into Modernism, as we can see from Gershwin to WH Auden, and Rivilious captures this with just a hint of this with his washed-out brushstrokes. Spalding writes, "Rivilious wanted to bring a modernist sentiment to watercolour painting". (Spalding 2022)

The idea that things happen in railway carriages is now firmly rooted.

As we pay more attention, we notice that the seats in the interior are opposite each other, as if inviting us in for a good, long conversation, where we can speak at length, listen and observe each other, and notice the slight shifts of energy and mood over time. Looking further also prompts us to consider whether there are more than one or two people in the carriage. Perhaps there are many. Maybe they sit without talking, barely unaware of each other's presence. They each carry baggage.

Like our minds, the carriage becomes a space that can accommodate our different selves, travelling in the same direction but perhaps getting on and off at other stations. Some travellers will stay for the whole journey, and some will be only brief companions, hopping off at the next stop. Perhaps some travellers are noisy and fidgety, while others doze under a newspaper. Some write furiously into a notebook; others gaze out of the window.

Perhaps there is harmony and communion, that beautiful moment where everyone seems to be together in a shared experience. But there's also a possibility of discord, conflict, avoidance, unappealing or unwanted fellow travellers shunned and excluded from the conversation.

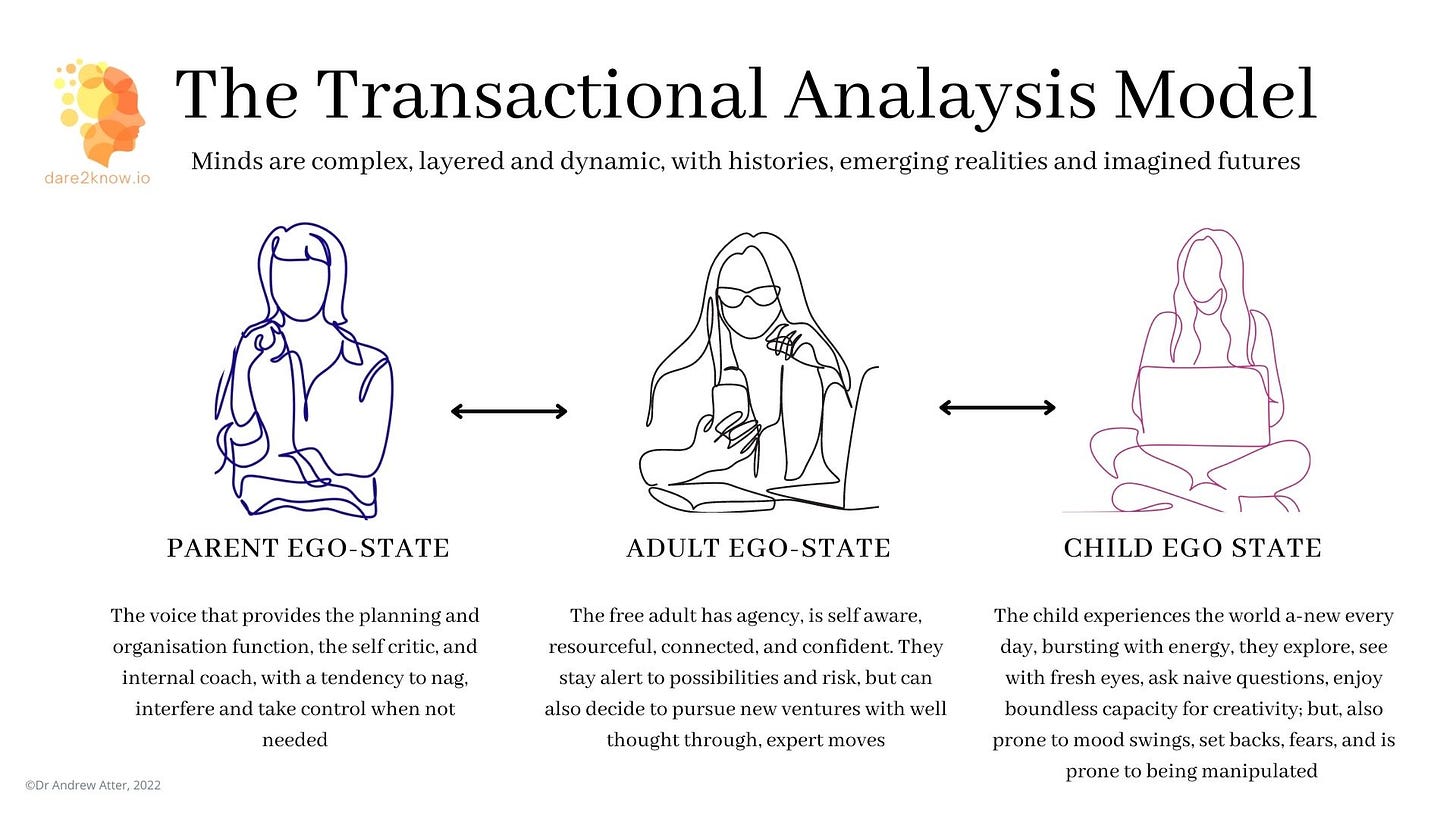

One seat faces forward, where the train is heading, facing the future. The other faces backwards to where we've come from. Yet another view is through the middle pane, seeing exactly where we are in this moment and able to view through all three windows equally. One can't help equate these three perspectives with Freud's id, ego and superego, later reformulated by Eric Berne (Berne 2010) as the child, adult and parent ego-states. The child looking forward expectantly. The parent looking back, forever aware of where you've come from and remembering your past mistakes. And finally, the adult can take in the scene, assess the situation, and decide where to sit and with whom to associate.

Back to the landscape, we're reminded that we're situated in an expanse of terrain that is both familiar to us in a general sense but unknown to us at a tangible level. We know that there is a strange archaic form, suggesting a history and evolution that we cannot fully understand or access. Freud, too, was obsessed with archaeology and saw psychoanalysis as a form of archaeology of the mind (Freud and McLintock 2002).

So, there are the outer and inner worlds, with the barrier defined by our ego states. The story or meaning of the journey is up to us. But perhaps we're not entirely in control of the narrative. Our fellow travellers will undoubtedly influence this. The facet of our personality, our various selves described by "internal family systems", are involved by the passing landscape, changes in the weather, and the imminent arrival at a particular destination.

Perhaps some younger, energetic self has already stepped off the train and is now just a pleasant memory. Or has a disagreeable passenger taken umbrage and gone to look for another carriage? Perhaps an entirely new version of ourselves will get on at the next stop and seek to take over the carriage, demanding a seat by the window and rudely taking up all the space with their luggage!

Perhaps if the goings-on inside the carriage is all too much, we can slide down the window and experience the wind rushing past our face, bringing freshness and sprite to our weary, stiff bodies. Despite the possible objections, it can be a good thing to let the outside world in, changing the flow of air and the direction of the conversation. The world can look different when we see it directly, and we no longer have the steamed-up windows between us and direct experience.

As Hitchcock showed us, things happen on trains.

Bibliography

Berne, Eric (2010): Games people play [electronic resource]. The psychology of human relationships / Eric Berne. London: Penguin.

Freud, Sigmund; McLintock, David (2002): Civilization and its discontents. London: Penguin (Penguin classics).

Hitchcock (1938): The Lady Vanishes. Starring Margaret Lockwood, Michael Redgrave.

Spalding, Frances (2022): The real and the romantic. English art between two world wars. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Auden, W.H; Jacobs, Alan. (2011) The Age of Anxiety, Princeton University Press